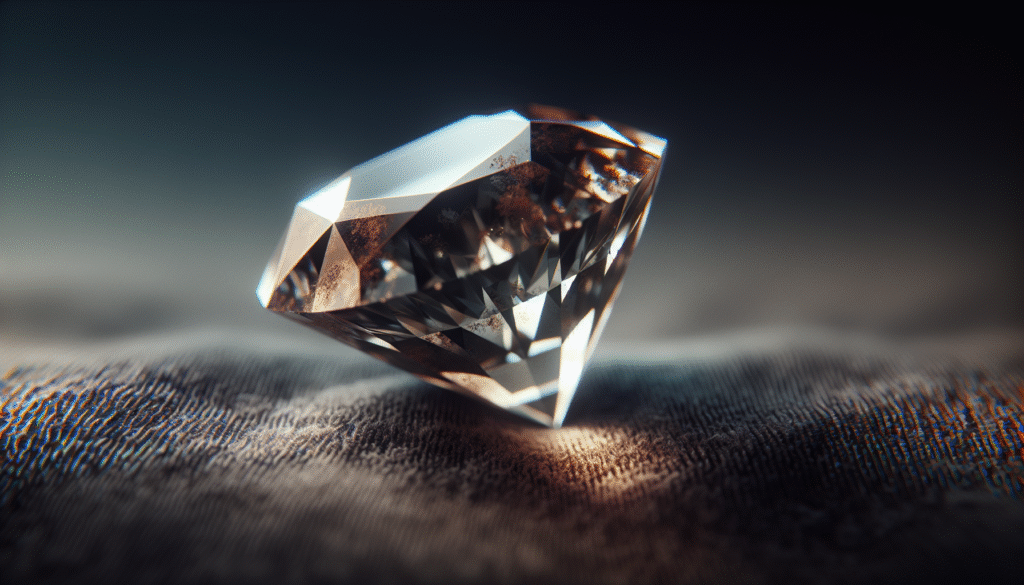

Have you ever squinted at a ring and wondered whether that stone is a diamond or a slightly smug grain of sugar?

What Are Low Quality Diamonds Called?

You’ll hear several names for diamonds that sit on the lower rungs of value and beauty, and the labels depend on the diamond’s defects or intended use. These terms range from technical grading categories like I1–I3 to trade names such as bort or boart, and knowing them helps you understand why a stone costs less or behaves differently in jewelry.

Why names matter

Names tell you about origin, use, and value, and they shape how the trade and consumers talk about stones. If you know what each label implies, you’ll stop worrying that the jeweler is whispering insults and start asking smart questions.

The core grading system: color, clarity, cut, and carat

When people talk about diamond quality, they return to the four Cs: color, clarity, cut, and carat weight. Each “C” affects price and appearance, and a weakness in any of them can earn a diamond a reputation as “low quality.”

Color

Color for white diamonds is graded from D (colorless) to Z (light yellow or brown). As you move toward Z, the stone can look increasingly tinted, and many consumers consider stones past K–L noticeably warm or faintly yellow.

Clarity

Clarity ranges from Flawless (FL) to Included (I1, I2, I3), with the “Included” grades representing visible internal flaws called inclusions. Those inclusions can range from tiny feathers hardly discernible under magnification to large crystals and fractures that interrupt the beauty of the gem with your naked eye.

Cut

Cut is about how well facets interact with light—not the shape, but the precision of proportions, symmetry, and polish. A well-cut lower-color or lower-clarity diamond can still look lively; conversely, a poorly cut high-color/clarity diamond can look dull.

Carat

Carat refers to weight, and more weight doesn’t automatically mean better appearance. Small stones with poor clarity or color still count as diamonds, but in groups like melee they’re valued differently.

Common terms for low quality diamonds

You’ll encounter both marketplace shorthand and formal grade names. The language varies by country, era, and even the mood of the seller.

Included grades (I1, I2, I3)

Included diamonds—those in grades I1 through I3—have inclusions visible without magnification. You can think of these as the “warts” group: they’re real diamonds, but their imperfections often change how they sparkle and can reduce durability.

Commercial-grade, industrial-grade

Commercial or industrial-grade diamonds were never intended to twinkle on your finger; they’re for cutting, drilling, or grinding other materials. If quality is judged by sparkle, these diamonds fail with elegance.

Bort / Boart

Bort or boart (historically spelled both ways) refers to lower-quality, often opaque or heavily included diamonds used chiefly for industrial purposes. In mining parlance, bort is the discard pile that earns a living by attacking rock rather than gracing a necklace.

Cape stones and historical terms

Old-time gem catalogs and nineteenth-century dealers used terms like “cape series” to describe yellowish diamonds from South Africa’s Cape Colony. Those labels are mostly historical now, but you’ll find them in antiques and auction descriptions.

Simulants and imitations

Simulants—such as cubic zirconia (CZ), glass, and certain plastics—imitate the look of diamonds but are not diamonds. Though not “low-quality diamonds,” they’re often mistaken for them by casual observers and by those who don’t bother checking the hallmark.

Treated and enhanced diamonds

Diamonds can be treated (fracture-filled, irradiated, or heat-treated) to mask defects or modify color. While treatments can make a diamond appear better, they usually lower value because the improvement isn’t natural or permanent.

A quick table: How grades relate to everyday look and use

| Category | Typical grade or term | How it looks to you | Common uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality | D–F color, IF–VVS clarity | Brilliant, eye-clean | Solitaire engagement rings, fine jewelry |

| Middle | G–J color, VS–SI clarity | Look good, some inclusions under magnification | Everyday jewelry, budget purchases |

| Low commercial | K–Z color, I1–I3 clarity | Noticeable tint or visible inclusions | Costume jewelry, low-cost pieces |

| Industrial / bort | Bort, boart, diamond grit | Opaque or rough | Cutting, drilling, abrasive tools |

| Simulants | CZ, glass, moissanite (not diamond) | Can look convincingly like diamond | Imitation jewelry, budget alternatives |

| Treated | Fracture-filled, HPHT-treated | Masked flaws or altered color | Discounted natural-looking stones |

You should use this table as a mental map rather than a rigid rule: many diamonds don’t fit neat boxes, and context matters.

What makes a diamond “low quality”?

When you hear “low quality diamond,” you should ask: low quality by what measure—beauty, durability, or market value? Those measures rarely align perfectly, and your use case determines whether a stone is truly “low quality.”

Visible inclusions

If inclusions are obvious without magnification, the diamond will struggle to sparkle and may chip or break more easily. You’ll see dark spots, clouds, or feathers that interrupt light pathways and reduce brilliance.

Strong coloration

A strong yellow or brown tint can make a diamond appear dull rather than bright. Some buyers like the warm tone; others equate color with cheapness, so perception is cultural as much as technical.

Poor cut and polish

A bad cut scatters light instead of returning it to your eye, creating a watery or glassy look that’s far from desirable. Even a flawless diamond that’s poorly cut can look “dead,” which many shoppers call low quality in practice.

Small size with poor finish

Small stones are often cut from leftovers and may carry irregular facets, poor symmetry, or leftover rough surface marks. These are fine for setting where they don’t get attention, but they’re unlikely to sing on their own.

How treatments change the conversation

Treatments are like cosmetic surgery for gems: they can produce immediate results but affect future value and care requirements. Sellers should disclose treatments, and you should ask to see proper documentation.

Fracture filling

Fracture-filled diamonds have surface-reaching cracks filled with glassy materials to mask inclusions. This can make a diamond look better at first glance, but the filling can be damaged by heat (from repairs) and is considered a significant value reducer.

Color treatments (irradiation, HPHT)

HPHT (high pressure, high temperature) and irradiation are used to remove or add color. While some treatments are stable and accepted, they typically lower the stone’s market value compared with naturally fancy or naturally colorless diamonds.

Laser drilling

Laser drilling removes black inclusions via microscopic tunnels, often followed by filling. It’s a subtle change that should be disclosed; it can improve appearance but won’t restore full value.

Real diamonds vs. simulants vs. lab-grown: the language trap

You’ll be told “real diamond” in the storefront like a benign accusation aimed at your judgment. The truth is messier: lab-grown diamonds are chemically and optically essentially the same as natural diamonds, while simulants only mimic the look.

Lab-grown diamonds

Lab-grown diamonds can have the same chemical structure and brilliance as mined stones and hence aren’t “low quality” by default. They are often cheaper, however, and some buyers conflate affordability with poor craftsmanship, which isn’t fair.

Simulants (CZ, glass, moissanite)

Simulants vary from convincing (CZ) to impressive in their own way (moissanite, which actually outshines diamond in fire). If you’re after the prestige or rarity of a mined diamond, simulants won’t satisfy that specific desire; for sparkle-per-dollar, they can be compelling.

How to tell them apart

Use a reputable lab report, a diamond tester, or a jeweler’s loupe. If a stone fogs up like a mirror after you breathe on it, it’s often not a diamond; if it’s too perfect at a suspiciously low price, you should request certification.

Bort, boart, and industrial diamonds: the workhorses

If your interest extends beyond jewelry to mechanics, you’ll appreciate bort and industrial diamonds for their toughness and hardness. These stones are judged by durability and particulate size rather than sparkle.

What bort looks like

Bort tends to be dark, opaque to translucent, and irregular in shape. It rarely ever finds its way into a fine ring because it gives up its gem qualities for practicality.

Uses in industry

From drill bits to saw blades to abrasive powders, industrial diamonds do jobs that would otherwise require crying and the antique lament of a jeweler who’s misplaced a fancied stone. They’re invaluable in manufacturing, not in seduction.

Historical and market perspectives

If you enjoy the idea that science and gossip intersect, the diamond trade’s lexicon tells stories of discovery, colonial trade routes, and marketing feats. Names like “cape” echo histories you can almost smell—the iron is cold, the ledger is crisp, and the dealer is already moving to the next person.

How language evolved

Terms that once helped miners sort rough stones became consumer labels and sometimes brand cues. Over time, laboratories standardized grading, but older terms still exist in catalogs, antiques, and auction houses.

Market implications

A treated or industrial stone suits certain markets but not the high-end consumer market. When you shop, the label will hint at resale value, insurance costs, and how jewelers will treat the stone during repair.

Practical buying advice: what you should ask and look for

You’re more likely to be content later if you ask the right questions now. Keep your expectations clear and your wallet closer.

Ask for certification

Always ask for a certificate from a respected lab (GIA, AGS, HRD). Certificates detail color, clarity, cut, measurements, and treatments, which helps you compare apples to apples instead of leaving things to salesperson charm.

Inspect in person with magnification

Look through a loupe or ask for detailed images. Try to see the inclusions, note tint, and watch how the diamond throws light in different angles; sometimes photos and words don’t tell the whole story.

Consider setting and budget

A lower-grade diamond can still be beautiful in the right setting—prongs, halos, and mixed metals can mask deficiencies and amplify sparkle. If your goal is maximum visual appeal for a budget, prioritize cut and eye-clean clarity over color grade.

Understand resale and insurance

Low-quality diamonds often have low resale value and higher insurance premiums relative to replacement cost. If that matters to you, opt for certified stones and keep paperwork safe.

Caring for lower-grade diamonds

If your stone has inclusions or treatments, it might require special care. Understanding simple precautions can extend the life of your piece and preserve its look.

Avoid extreme heat and chemicals

Fracture-filled diamonds and some treated stones can be damaged by soldering—make sure any jeweler knows the stone’s treatment status before repairs. Routine cleaning with mild soap and water is typically safe, but ask your jeweler about specifics.

Regular check-ups

Inclusions and fractures can become worse with impact. Regular inspections can catch security and structural issues before they worsen; small problems become less dramatic if they’re found early.

Ethical and environmental considerations

You may think low-quality diamonds are a scrap byproduct, but mining impacts and ethical sourcing still matter. The price tag doesn’t absolve any stone from the consequences of how it was extracted.

Conflict and traceability

Certification and chain-of-custody systems help you avoid stones tied to conflict. Even low-grade stones can be mined in harmful ways, so ask about origin or seek retailers who guarantee ethical sourcing.

Environmental footprint

Smaller or lower-quality stones may come from the same operations as high-quality ones, meaning the environmental cost isn’t less because the gem is imperfect. Lab-grown options present a different set of environmental trade-offs to consider.

When a “low quality” diamond is still the right choice

You aren’t trying to impress a crown; you want something pretty, durable for daily wear, or affordable enough that you won’t faint when washing dishes. Low-grade stones can be great choices depending on your priorities.

Functional jewelry and fashion

For bracelets, cluster rings, or trendy pieces with many small stones, lower clarity or color in melee stones is common and often unnoticeable. That means you can get significant sparkle for less if you accept the trade-offs.

Sentimental value trumps grade

A family heirloom diamond with visible inclusions might not earn top market value, but if it carries a story, you’ll value it more than a flawless stone purchased this afternoon. Sentimentality often outpaces clarity charts.

Quick identification tips for consumers

You don’t need a gemological degree to spot some giveaways; a few simple checks can save you from regret.

- Ask for a certificate from a recognized lab and read it.

- Look for signs of filling or unusual patterns under magnification.

- Use the fog test: diamonds disperse heat quickly and won’t fog like glass.

- Watch the stone under different lights; color and brilliance shifts reveal a lot.

Each method has limitations, so use them together rather than relying on a single trick.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

You’ll likely have quick questions during shopping and quick answers help you choose without melodrama. Here are common ones and blunt but polite replies.

Are low-quality diamonds real diamonds?

Yes. Many stones labeled “low quality” are genuine diamonds with more inclusions, poorer color, or both. The difference is in aesthetic and market value, not the basic chemistry.

Can a low-grade diamond be repaired or improved?

Some treatments, like laser drilling or fracture filling, can improve appearance temporarily, but these interventions reduce value and can require care. Permanent improvement is limited—sometimes recutting helps but at the cost of weight.

Is an I3 diamond a waste of money?

It depends on your priorities. If you want everyday sparkle and cannot tolerate visible inclusions, an I3 may disappoint; if you want a diamond that serves as a token or will be set among other stones, it may be fine.

Are black diamonds poor quality?

Not necessarily. Natural black diamonds (carbonados) have distinct structures and are often opaque; some are used in jewelry as a stylistic choice rather than a low-quality substitute. Market value depends on rarity and desirability.

Should you buy a simulant instead?

If your goal is head-turning sparkle without the prestige, simulants like moissanite or CZ can be economical and attractive. If you value authenticity, insist on a certified natural or lab-grown diamond.

Glossary: short definitions you’ll actually read

- Inclusion: An internal feature within a diamond, like a tiny crystal or feather.

- Bort/Boart: Lower-quality diamond material used mostly for industry.

- Simulant: A non-diamond material that imitates diamond appearance.

- Fracture filling: A treatment to hide cracks using a glass-like substance.

- HPHT: High Pressure, High Temperature treatment that can change color.

- Melee: Small diamonds usually used as accent stones in settings.

Each term matters when you’re negotiating price, asking for repairs, or deciding whether a family trinket should be reset.

Final thoughts

You’ll find that “low quality” is a label that depends on perspective. A diamond with an I2 clarity grade might make you smile if it’s affordable and set cleverly, while a flawless stone might make you look like a person who insists on the best at all times. Remember that certification, honest disclosure about treatments, and a jeweler you trust will protect both your money and your taste. If you stay curious and ask the right questions, you’ll end up with a stone that suits your life—whether it’s a sparking solitaire, a sentimental heirloom, or something tough enough to drill through the day.